Leicester City didn’t play Ipswich Town at all until Boxing Day 1961, when we travelled to Portman Road to face the team that would win the First Division title for the first and only time the following April.

So in the 1962/63 season, our first away win over Ipswich came against the reigning champions of England.

The date was 6th October 1962, the day after “the day that changed Britain” which saw the premiere of the first James Bond film, Dr No, and the release of the first Beatles single, Love Me Do.

As John Higgs said in his recent book “Love and Let Die: Bond, the Beatles and the British psyche”:

“Most countries can only dream of a cultural export becoming a worldwide phenomenon on this scale.

For Britain to produce two on the same windy October afternoon was, by anyone’s standards, unusual.”

Later that month, the Cuban Missile Crisis gripped the world – and Alf Ramsey was appointed England manager.

We’re going to start back in 1959, long before anyone could think it was all over, when a book was published called ‘Young England’. It detailed where English football was going wrong, where it was going right, and focused on the promising youth internationals who might be able to make the step up to bring England the glory it craved on the biggest stage of all. It’s a reminder that there were years of hurt before 1966 as well as after.

The author of Young England was a certain Kenneth Wolstenholme. In the index, the names of 291 men are listed – ranging from Pele, Bobby Charlton and Stanley Matthews to Gerry Cakebread, Franklin Twist and Bedford Jezzard – an array of players who had made it, who would make it, who never quite did.

Duncan Edwards, who had died the year before in the Munich air disaster, is repeatedly held up as a tragic example of lost potential. Among the Cakebreads, Twists and Jezzards, there are also those who went on to greatness. Bobby Moore is singled out for his impressive performances in the International Youth Tournament of 1957/58.

Alf Ramsey gets a couple of mentions, although only in relation to his playing career. What Wolstenholme couldn’t have known then is how the young Ramsey was learning things he would implement after his playing career finished.

In his outstanding history of football tactics Inverting the Pyramid, Jonathan Wilson explains the influence, both direct and indirect, that Hungarian football in particular had on Alf Ramsey and his future success managing for club and country.

Wilson traces the lineage of Ramsey’s tactical evolution back to a trip made by a man named Arthur Rowe to Eastern Europe in 1940. Rowe was able to use some of the tips he picked up from Hungarian football while lecturing in Budapest when he became manager of second division Tottenham Hotspur in 1949.

While Rowe’s experience of the 1940s took him from Eastern Europe to the Tottenham job, Ramsey juggled football with the commitments of war. He had been conscripted to the British Army in June 1940 and, having not been sent abroad during the Second World War, his performances for a Battalion football team against Southampton saw him signed by the south coast club.

In December 1945 after the war had ended in Europe, Ramsey was deployed to Mandatory Palestine. In 1946, he captained a Palestine Services XI that also contained future Leicester goalscoring hero Arthur Rowley.

One of Rowe’s first acts as the new Spurs manager in the summer of 1949 was to sign Ramsey, who had just fallen out of favour at Southampton following a knee injury. Rowe encouraged Ramsey to consider his passes more carefully rather than carrying out the usual hoof upfield favoured by most teams.

Tottenham started playing out from the back, almost unheard of in England at the time, in a new style labelled “push and run”. This freed Ramsey to go on the attack far more than most right-backs of the age.

The immediate reward for Tottenham was back-to-back league championship titles – the Second Division in 1950, the First Division for the first time in the club’s history the following year.

The additional benefit to Ramsey and the two sides he would go on to manage took a bit longer. Before that, he would get a more direct lesson from the Hungarians.

On 25th November 1953, England played Hungary at Wembley and Alf Ramsey was selected at right-back. England had been beaten only once at home by foreign opposition before this game. They would be humbled by the Hungarians. Ramsey scored a penalty in the 57th minute, the only problem being that the visitors were leading 6-2 when he stepped up to the spot.

Ramsey’s goal was the final one, Hungary winning 6-3 to cause a seismic shock to English football in an encounter subsequently labelled “The Match of the Century”. It is commemorated in Budapest by a giant mural.

It was an immediate turning point for Ramsey, who never played for England again. Both his and Tottenham’s fortunes were in sharp decline. By 1955, shortly after what he called “a terrible roasting” from Leicester winger Derek Hogg during a 2-0 win for the home side at Filbert Street in April, his switch from player to manager would be complete. In August, he was announced as the new manager of Ipswich Town – then in the Third Division (South).

As Jonathan Wilson says in Inverting the Pyramid:

“Results soon picked up, but it wasn’t until December that Ramsey made the switch that would set in motion a decade of evolution that ended in the World Cup. Jimmy Leadbetter was an inside-forward, a skilful, intelligent player whose major failing was his lack of pace.

He had been signed in the summer by Ramsey’s predecessor Scott Duncan and, having played just once in Ramsey’s first four months in charge, was concerned for his future. Then, just before New Year, Ramsey asked Leadbetter to play on the left-wing. Leadbetter was worried he wasn’t fast enough, but Ramsey’s concern was more his use of the ball.”

Ramsey requested that Leadbetter played as a deep left-winger, collecting balls from the defence far deeper than opposition full-backs were comfortable to pursue him. As he moved forward, the full-back would be drawn out of defence to mark him leaving space for centre-forward Ted Phillips to roam free.

Phillips scored 46 of Ipswich’s 101 goals as they won the Third Division (South) in 1957, the same year that Leicester won the Second Division with Arthur Rowley netting 44 of their 109 goals.

In the 1957/58 season, Leicester would avoid relegation from the top flight thanks in part to Rowley’s 20-goal haul – but Rowley and Ramsey would not face each other as player and manager. Rowley was transferred to lower league Shrewsbury Town in the summer of 1958, while Ipswich were embarking on several seasons of consolidation in the second tier.

8th, 16th, 11th – there was little in Ipswich’s Second Division league positions between 1958 and 1960 for people to foresee what would happen between 1960 and 1962.

But either side of that period Ramsey picked up players who would play a crucial part in what followed. In 1958, the 22-year-old centre-forward Ray Crawford joined from Portsmouth. In 1960, Leicester allowed right-winger Roy Stephenson to move to Portman Road.

And in the 1960/61 season, Ipswich stormed the Second Division. Crawford top scored with 40 goals in a team that struck a round century in total.

In their first-ever season in the top flight, Ramsey’s Ipswich remarkably repeated the trick. The team scored seven fewer and Crawford three fewer but they were still staggering numbers. Ipswich finished three points clear of second-placed Burnley and four clear of Tottenham in third, then managed by Ramsey’s former Spurs team-mate Bill Nicholson whose dour defensive nature as a player had allowed Ramsey outside him to attack.

Ramsey’s Leadbetter tactic from 1957, with former Leicester winger Stephenson’s role also integral on the other flank, was still working a couple of divisions higher up in 1962.

But at the start of the 1962/63 season, Ipswich faced a similar problem to another shock top flight winner 54 years later. Teams who had been caught out by an unusual tactic knew what to expect second time around.

As Wilson explains, that began even before the league season thanks to Ramsey’s team-mate turned managerial adversary: “Ipswich lost the Charity Shield 5-1 to Spurs as Bill Nicholson had his full-backs come inside to pick up the two centre-forwards, leaving the half-backs to deal with Leadbetter and Stephenson. Other teams did similarly.”

Ipswich won just two of their opening 11 league games in August and September 1962. The comparison with Leicester’s 2016/17 campaign is obvious – Claudio Ranieri began that season with three wins from the first 14 played before the end of the Champions League group stages.

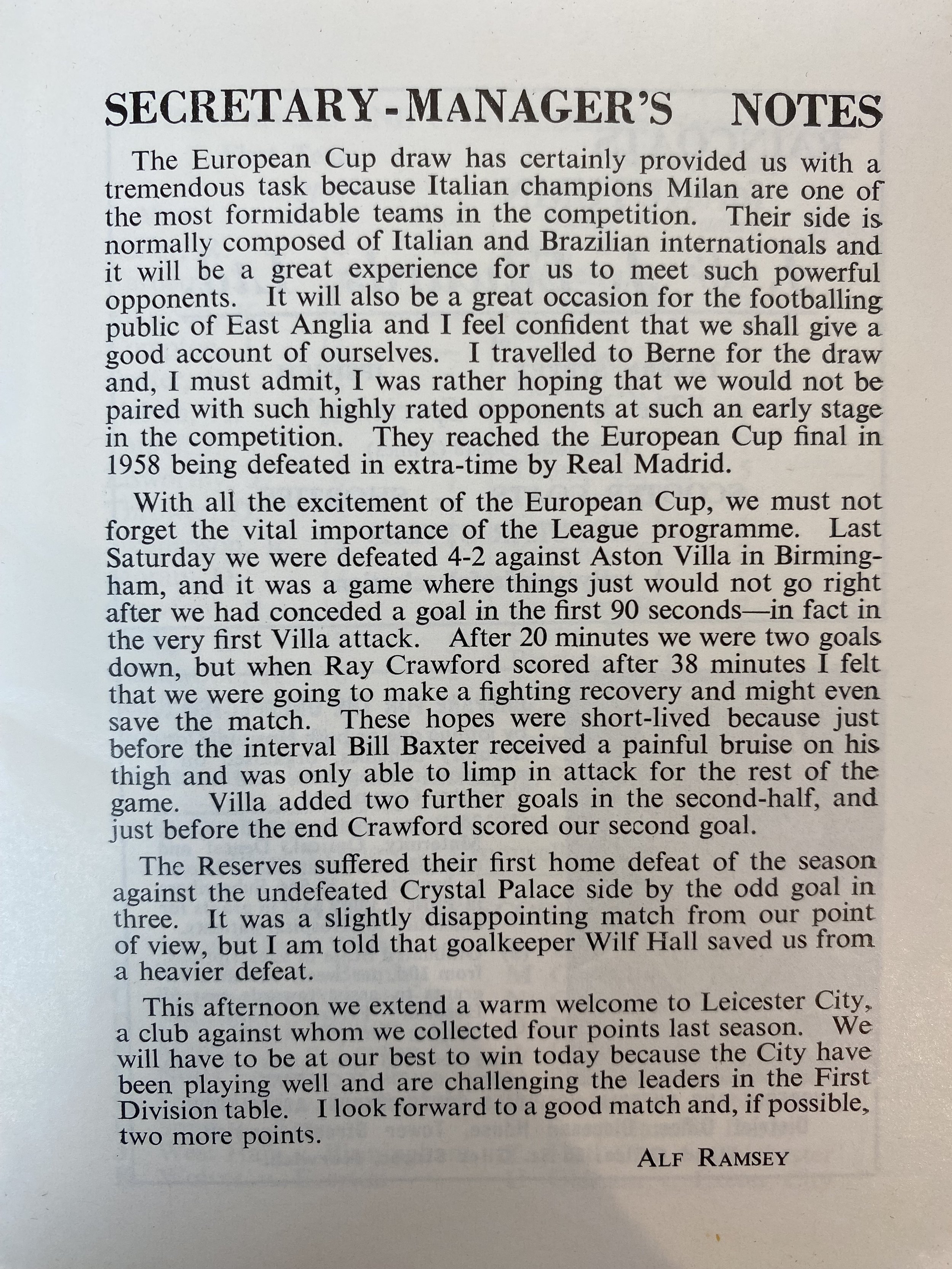

Ipswich also had Europe to contend with in 1962. They won their previous game 10-0 against Maltese side Floriana in the European Cup and anticipation was already building for their next tie against AC Milan.

On the morning of the league clash with Leicester in October, the Leicester Daily Mercury published an editorial titled ‘Soccer Dons’:

“English sportsmen have been swallowing bitter pills over the last 15 years every time an English side has been beaten, sometimes heavily beaten, by a foreign team. The galling fact has had to be faced – England, the nation that started football and gave it national and international status, has not been near the top since the war.

The new moves by the Football Association to improve playing standards are therefore being carefully watched. The decision to split up Walter Winterbottom’s former joint appointment as England manager and chief coach is probably the most significant. And the choices of the four candidates on the chief coach short list emphasises another aim – three of those shortlisted are college trained, men who can coach both on the field and in the lecture room.

There is no suggestion here that the FA favours Russia’s Master of Sport build up – the super professional – nor is an academic approach to football intended. But the fact remains that the art and science of both coaching and playing are to be given more than touchline treatment. So it’s notebooks as well as boots for England players in the future – and, it is hoped, higher rating in international football affairs.”

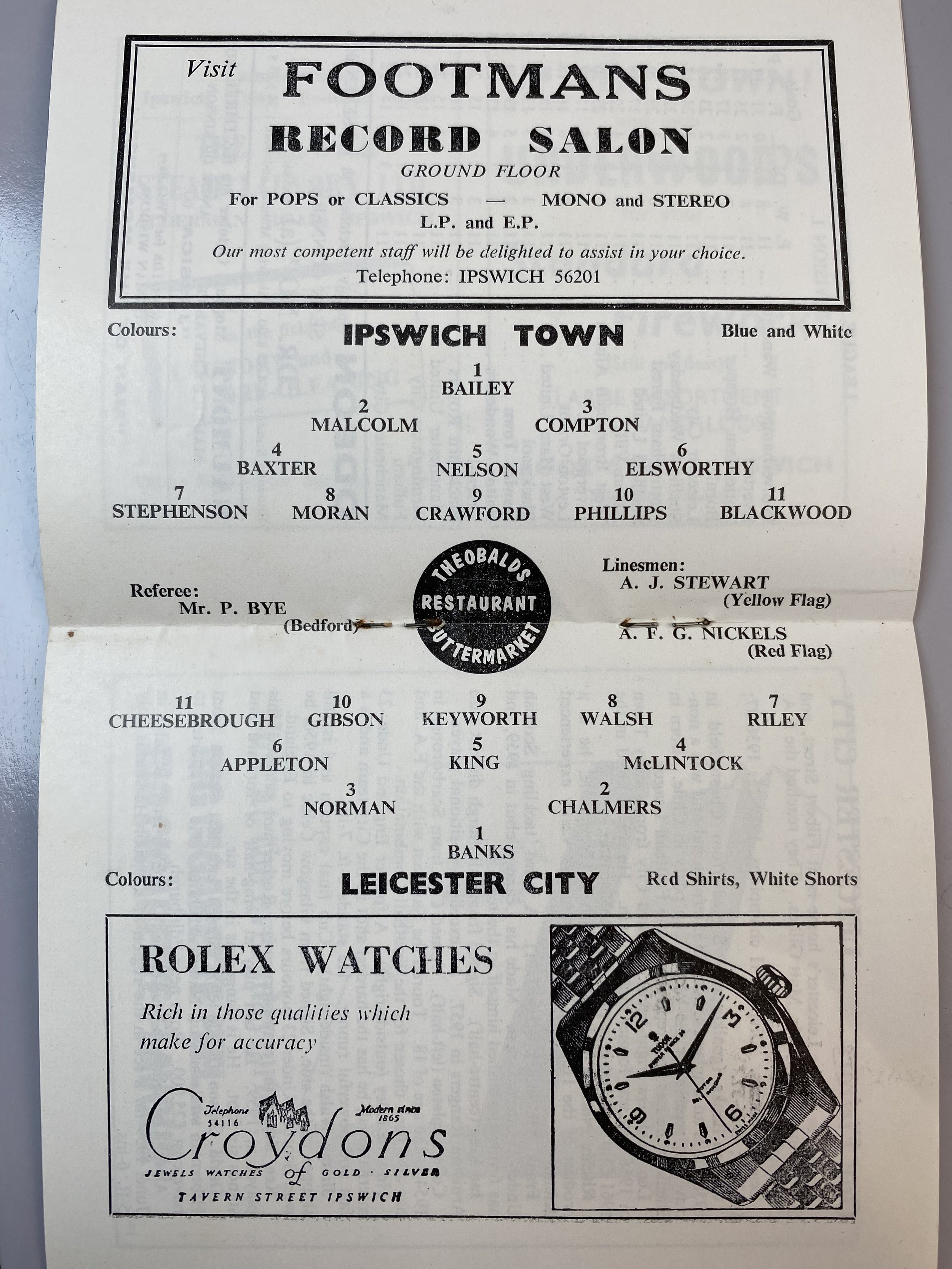

Leicester had our own offering to boost the national side’s fortunes, Gordon Banks, who was touted as an “England hopeful” in the Daily Herald’s report of Leicester’s trip to Ipswich.

In front of him, the absence of star inside-left Davie Gibson through illness left manager Matt Gillies with a reshuffle to perform. Gillies moved Frank McLintock from wing-half to inside-forward and Graham Cross shifted from centre-forward to right-half in place of McLintock.

Multiple reports paid tribute to the state of the Portman Road pitch as being comparable to Wembley Stadium, with 19,000 fans enjoying the unseasonably warm weather in Suffolk.

In his Saturday afternoon report for the Leicester Evening Mail, Billy King said:

“The game’s first big thrills involved Banks. He swept away a dangerous oblique header from Crawford, ex-England leader, then made a brilliant save from Phillips.”

Leicester withstood a barrage from the Ipswich attack and with ten minutes remaining, they delivered the sucker punch. McLintock was the goalscorer, steering in through a crowded penalty area after Ipswich goalkeeper Wilf Hall, who had surprisingly replaced their usual number one Roy Bailey, failed to gather in a corner.

Bailey was one of a group of five Ipswich players, also including Jimmy Leadbetter and Ted Phillips, to become the first to win the title in each of the top three divisions of English football – a feat only since repeated by Leicester’s Andy King.

At Portman Road, praise was lavished on another Leicester man who would go on to be long-serving. Laurie Simpkin’s report for the Leicester Mercury highlighted the performance of defender Graham Cross “in his first senior outing at No. 4”. Cross, who had made his Leicester debut in 1960, was still early in his Foxes career. He would play a record 600 times in all competitions across 16 years with the club.

Cross and McLintock’s shift in positions for the game at Portman Road foresignalled a tactical tweak that almost brought Leicester City a League or FA Cup trophy far before the days of Andy King.

And again the Hungarians were to thank.

Leicester coach Bert Johnson had, like Arthur Rowe and Alf Ramsey, been influenced by the Mighty Magyars of the 1950s and helped Gillies to implement a plan involving Cross and McLintock switching positions mid-game. With players still in the habit of looking for the number on the back of their direct opponent’s shirt, this caused chaos and helped Leicester defeat Bill Shankly’s Liverpool in the 1963 FA Cup semi-final.

As for Ipswich’s own response to defeat at Portman Road in October 1962, the Daily Herald’s report was clear about what the result meant for the hosts’ hopes in Europe:

“The man in the crowd uttered a string of unkind words about the players he cheered last season, then added: “European Cup? Huh, Milan will murder them.”

Ipswich did indeed go out over two legs to AC Milan the following month. The Italian side went on to win the 1963 European Cup final at Wembley against Benfica in May. That game took place three days before Leicester, who had beaten Ipswich along the way before seeing off Shankly’s Liverpool, lost the FA Cup final at the home of English football to Manchester United.

This was the same month that Ramsey took up the England role he had agreed the previous October. Gordon Banks was the new England number one by this point, having made his debut in April 1963 against Scotland at Wembley.

Their fortunes would converge on a day when so many men reached their career peaks on the same day – 30th July 1966: Ramsey, Banks, Kenneth Wolstenholme and that young West Ham prospect Wolstenholme had highlighted seven years earlier to mention just four.

By then, Ipswich were back in the Second Division. They were promoted back to the big time two years later and finished as runners-up in both 1981 and 1982, but their sole top flight title remains that 1962 triumph.

Ipswich Town lived the dream in the early 1960s, achieving incredible success thanks to Sir Alf Ramsey and his band of overachievers. A similar feat took place at the end of the following decade – before both were topped by the greatest footballing underdog story of all.

document.getElementById(‘newsnowlogo’).onclick=function(){ window.open(‘https://www.newsnow.co.uk/h/Sport/Football/Premier+League/Leicester+City’,’newsnow’); }; document.getElementById(‘newsnowlogo’).style.cursor=’pointer’; document.getElementById(‘newsnowlogo_a’).style.textDecoration=’none’; document.getElementById(‘newsnowlogo_a’).style.borderBottom=’0 none’;

A 2-0 win against Southampton finally moves the Foxes past the 20-point mark.