What’s going wrong? Studying Leicester City in and out of possession

With only a single point in six games, Leicester City find themselves at the foot of the Premier League table. The general view of the fanbase is increasingly pessimistic, perhaps at an all-time low since the King Power conglomerate bought the club, with many fans calling for Brendan Rodgers to be sacked.

This article isn’t attempting to persuade the reader one way or the other, but it will attempt to highlight some of the “footballing issues”, focusing on the team’s movement both in and out of possession.

For this article, I will be generalising movement into two distinct categories.

For the “out of possession” segment, I will be focusing on Leicester City’s usage of a defensive block and their consequential pressing structure. The “in possession” segment addresses the attacking movement off the ball, from players who are attempting to support and aid the ball-carrier.

There’s more to movement than these two broad sub-sections, but the recent game against Manchester United highlighted a few clear conceptual problems for the Foxes. Therefore, these will be the focus of this work.

Out of possession

Without the ball, Leicester follow the basic principles that most clubs in the Premier League follow. The position of the defensive block would be considered “mid”, rather than high or low - suggesting that they control the middle section of the pitch with their defensive unit.

They attempt to press once a selected trigger is set. This will change depending on the opposition, and the intensity of the press will ebb and flow throughout a game but ordinarily, Rodgers asks for high intensity to start, and the players lower it as fatigue kicks in.

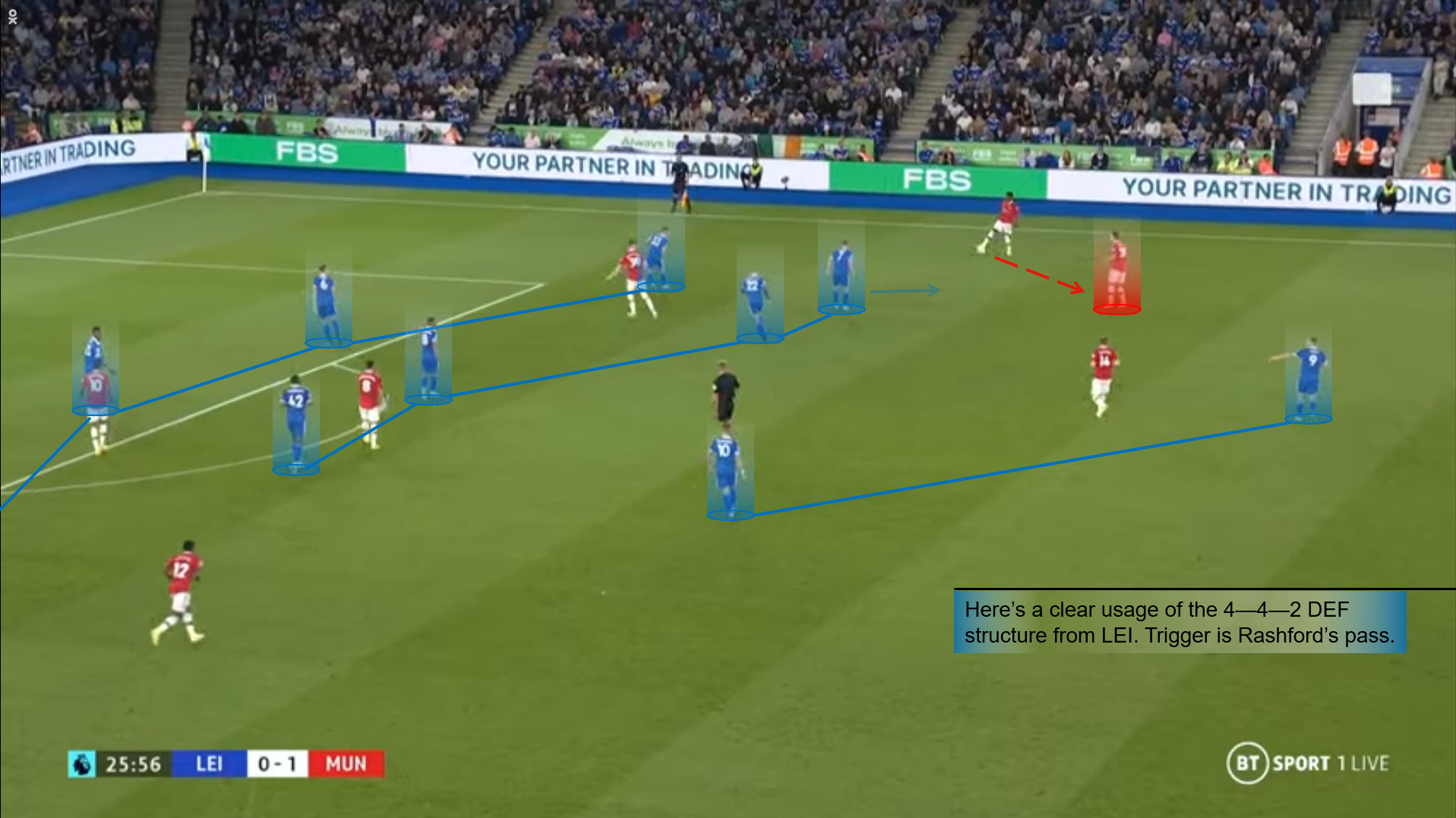

An interesting part of Rodgers’ mid-block is that Leicester adopt a 4-4-2 defensive formation, even when using the 4-3-3 structure in possession. To achieve this, they will simply reposition the “advanced midfielder” – in this example, James Maddison (the right-winger) – to accompany Jamie Vardy in the first line of the block. Even if the Foxes use different formations for their attacking structure, they very often play inside of a flat 4-4-2 defensively.

If you remove all the other tiny details and nuances, the simplicity of this is that you give every player a clear opponent to mark. The “strikers” (Vardy and Maddison) have to deal with the centre-backs; the wingers are covering the full-backs; the midfield matches up; and then you have full-backs on wingers, and centre-backs on strikers. This simplification is good, especially during moments of vulnerability for Leicester – like this current run of form.

Against Manchester United, the pressing trigger was seemingly backwards passes, or a pass that would take the receiving player closer to their own goal. I would suggest that the advantage of doing this, especially against a side like United, is that you’re slowly forcing a pass into their goalkeeper. The press initiates after a United midfielder or full-back passes into the centre-backs, and by applying pressure at this moment you limit how many passing angles the recipient has.

By isolating them, they will often have only two options: clear the ball long or pass backwards to the goalkeeper. With David de Gea between the sticks for Erik ten Hag’s side, you have a goalkeeper who is statistically very poor with the ball at his feet and this style of pressure is aimed to expose this. However, in the below example, bad initiations of this pressing trigger caused problems for Leicester.

The activating pass was from Marcus Rashford, who played a short - but importantly, backwards - pass into Diogo Dalot. This pushed Harvey Barnes into initiating a press, but he didn’t activate quick enough and allowed a simple pass back into Rashford. This sequence works like dominoes: Luke Thomas pressed onto the receiver (Rashford), but he also mistimed this and the pass could go inside to Scott McTominay. Kiernan Dewsbury-Hall and Youri Tielemans activated on this pass, probably due to how close United were to entering the penalty area, and this freed an easy pass into Christian Eriksen.

A lot of Rodgers’ post-match comments from the Chelsea game were surrounding his frustrations with Leicester conceding shots at the top of the box uncontested. In this example, Eriksen - one of the league’s best from this sort of location - was given licence to shoot. Thankfully, it was on his weaker left foot and didn’t really trouble Danny Ward. However, this shot was available due to bad usage of the block into a press – had Eriksen noticed Jadon Sancho open on the left wing, United could’ve had a high xG chance on goal.

There are plenty of other examples of Leicester activating out of the block into a press at the wrong time, or out of sync. The key to success in pressing teams is to be organised and structured.

But there’s also another principle that I see Rodgers’ side get wrong quite often, and that’s the use of “cover shadows”. I will provide an illustrated example below, but first: what is a cover shadow? It’s the space behind your pressing player that they control, rather than the opposition, since passing straight through a player is almost impossible. Understanding this fundamental element when applying pressure is very important.

Leicester occasionally use this practice well. Unfortunately, most of the time, they ignore it.

In the example illustrated below, Leicester placed the first two players of their pressing shape (Vardy and Dewsbury-Hall) high because De Gea was on the ball. Instead of using cover shadows and effectively “marking” some of his options by covering the space for a pass into them, while also putting pressure on the keeper by pressing him as well, the two players just sat high and were easily bypassed.

If you look at the referenced time stamps, both Leicester players sat in this position for six seconds (it’s a lot longer than you think), while United’s players were moving to create space for De Gea.

The structure here was very poor – these players are useless in the first line of the press and didn't force any mistakes from United’s defenders. This resulted in easy progression through the pitch and eventually United found themselves in the final third, far too easily. Leicester struggled to replicate this building pattern because United’s players individually used cover shadows more proactively while pressing - it’s as simple as that.

I’ve provided one final example of bad, or what I’d refer to as “wrong”, defensive movement. It's a blend of the two ideas – pressing initiation from the block, but also not using cover shadows. The end product is displayed in the sequence below.

Although the pressing trigger against Manchester United was a backwards pass, Raphael Varane’s ball to Dalot (misplaced, which forced him to retreat towards the touchline) should’ve worked as a trigger for Leicester. Instead, this was recognised too slowly and let Dalot safely reclaim control of the play – Vardy’s positioning (the sole striker in the 4-3-3, because this sequence just followed a turnover of possession) was too central, meaning he covered nothing.

The domino effect of late presses from the likes of Thomas, Dewsbury-Hall and Tielemans meant that passing lanes remained open for every United player receiving possession, while those further ahead in the pressing shape – Barnes and Vardy – didn’t cover any players with their positioning or cover shadow combination. It made them useless in this phase of play.

It might seem nit-picky, but these are errors that the good pressing teams in the Premier League don’t make. In most pressing sequences, Leicester have a few players who I deem to be completely ineffective (for that sequence); having a single player out of a sequence is difficult enough for the remaining players to carry, but multiple players out makes these defensive situations almost impossible - especially for the centre-backs, who become increasingly isolated.

In possession

Unfortunately, it doesn’t get much better on the reverse side of the ball when Leicester attack, but there are slight improvements. Nonetheless, I will try to highlight some of the problems from an attack positioning and movement stance, to help provide you with an understanding of why Rodgers’ side seem to struggle in possession.

The annotated example below shows two very distinct situations for the Foxes. Firstly, the lack of movement (or positioning) of the second line of midfielders and forwards means they fail to create pockets of space to pass into, while the first line of midfielders aren’t making enough effort to help the centre-backs. Secondly, how having an excellent vertically progressive passer – in this example, Boubakary Soumaré – can solve this, to ensure there are still ways to play through the pitch.

What I liked about showing this sequence was that it highlighted both the negatives of Leicester's movement and also how they’ve shoehorned in progressive moves throughout the opening few games - it’s not textbook but it’s a small solution.

Finding Tielemans as the second receiver (Soumaré being the first) enabled the quick verticality that freed Maddison to carry into the final third. Without being too negative, Leicester really squandered this play with some poor pass execution and a lack of ideas around the box.

It’s imperative for the midfielders to come and show for possession, to enable a pass through the first line of the press. Instead – and this was evident in the example – Soumaré offers for possession deeper than the first line. Without his verticality on the ball, he’s removed himself as a receiver and made progression more difficult. As we can see, though, he’s capable of playing through the lines to make up for it.

It’s also on the more advanced players; Maddison, Barnes, Dewsbury-Hall (the three “midfielders” behind Vardy) to offer in pockets of space through the lines. If they’re available, the sequence can skip the initial phase and directly progress into the middle-to-final third.

Unfortunately, the current movement is extremely poor. That's probably a by-product of confidence, or maybe fear of losing possession because of the fragility in defence, but ensuring that there are easier ways for Leicester to play through the pitch and create shooting opportunities is a fundamental issue at the moment.

In fact, finding team-mates inside the opposition area has also been difficult for Rodgers’ team this season. He’s given the majority of his available forward minutes to Vardy (77.4%), but statistically this is one of the 35-year-old’s worst starts to a Premier League season.

To get a better understanding of what’s going wrong for the talisman, I decided to create a dashboard to look at Vardy – addressing his locations for touches (as he’s the main receiving player of progression for Leicester, so ensuring he maintains the ball is of upmost importance to retaining possession with verticality), but also looking at his actual goal threat. Statistically, this is at its lowest point since the 2014/15 season, when Leicester were a newly-promoted Premier League club.

When receiving the ball, Vardy keeps possession 50% of the time. I haven’t run the numbers on other forwards playing as a “9” in the Premier League, but this seems below average. The location for his touches is very deep, with just 5 touches inside the area.

I didn’t include his involvements inside the defensive penalty area, as this would skew the results, and I’ve also not included any offside touches or short passes he completed inside the defensive third. The idea was to illustrate his connectivity as an advanced receiver of the ball, so the deep connections are irrelevant.

Then you look at his shooting data: just five shots in the opening six games of the season, with four of these in one game against Chelsea (and crucially, this was against 10 men). After six gameweeks, he’s recorded just 1.04 xG and doesn’t look like rectifying this with his lack of shots and presence in the box. It’s a very bad look, especially when you compare this with his heights in previous seasons.

The problem isn’t all on Vardy, though. Far from it, actually – it’s about having the creativity behind him to solve these conundrums, something Rodgers has ultimately struggled to do throughout his managerial career. That's not due to a lack of tactical understanding – he’s a very smart coach – but more through overcomplicating the process with players and actually losing some of them with his lack of man-management.

Perhaps that’s his biggest issue to date.